|

|

|

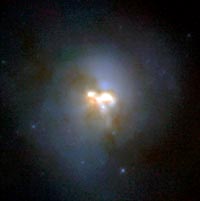

| A near-infrared image of the peculiar galaxy Arp 220 from the Hubble Space Telescope. More luminous than 100 Milky Ways and radiating most of its energy in the infrared, Arp 220 is a ULIRG. It is likely the result of a collision of 2 spiral galaxies. |

|

NASA’s Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS) discovered a new class of galaxies that are as much as 100 times more luminous in the infrared than they are in visible light, rivaling quasars in total luminosity. Astronomers named these galaxies Ultra-Luminous InfraRed Galaxies (ULIRGs). ULIRGs are found in merging galaxies whose collisions lead to dust-enshrouded bursts of star formation. WISE will find ULIRGs all over the sky, out to distances and lookback times where

most galaxies were still forming.

When galaxies collide the interstellar gas and dust within them compresses and regions of it become dense enough to collapse under the force of gravity. These collapsing regions are where stars will form. The clouds where the stars form are so massive and dense that the star formation regions are completely obscured by dust. Visible and ultraviolet light from the new stars is absorbed by the dust which heats up and then radiates that energy in the form of infrared light.

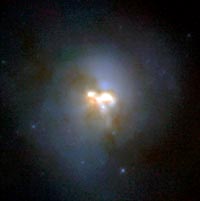

| This ultraviolet, visible, and near-infrared composite image from the Hubble Space Telescope shows the ULIRG IRAS 19297-0406. The collision of galaxies that formed this new galaxy has ignited a burst of star formation, producing about 200 new Sun-like stars every year—about 100 times the rate of star formation in the Milky Way. |

|

|

|

Some ULIRGs may also be powered by more than prodigious star formation alone. Indeed, the most luminous ULIRGs may be powered by supermassive black holes consuming matter in the hearts of the galaxy mergers. The disk of matter that spirals down into such a black hole may be surrounded by clouds of dust, which obscures the disk in visible and ultraviolet light and reprocesses the higher energy light into infrared.

ULIRGs tend to be found both near and far. But, previous studies have suggested that they are more plentiful at greater distances. That would indicate that they were more common in the past and have died out with time. The best explanation for this is that since the observable Universe was smaller in the past, galaxy collisions and mergers were more common then than they are now. As the ULIRGs aged they ran out of gas and dust with which to form new stars, and their super massive black holes ran out of material to consume in their vicinities. Thus, the luminosities of ULIRGs would diminish over time and their shapes would also become more regular as the stellar orbits within settled down. It is possible that nearby (i.e. recent) elliptical and lenticular galaxies are the evolved states of many ULIRGs.

|

| The lenticular galaxy NGC 2787. This disk-like galaxy—imaged in visible light by the Hubble Space Telescope—contains little dust or gas, has no appreciable spiral structure or ongoing star formation, and may contain a massive black hole in its nucleus that is quietly consuming small amounts of matter. This galaxy, and others like it, may be the late stages of a ULIRG. |

|

WISE will be sensitive enough to detect the most luminous ULIRGS out to a lookback time of when the Universe was only 3 billion years old. Some models of the Universe suggest that this is before the bulk of star formation occurred in the history of the Universe. Even if this is not quite so, smaller galaxies would have formed first and then later merged to form massive galaxies like ULIRGs. Since WISE will have the sensitivity to detect ULIRGs out to such great distances and will survey the entire sky, it will likely find the single most luminous galaxy in the observable Universe.

|

|